An Atomic Future?

“Modern civilization is built on energy, and the more complex the system, the more energy it requires.” – Vaclav Smil, Professor

Enthusiasm for artificial intelligence continued to propel markets in 2025. With each new large language model (‘LLM’) release beating prior benchmarks, expectations for AI’s transformational impact are raised. Beneath this excitement sits a familiar question, one that has accompanied almost every major technology boom. When will investors see a return on the extraordinary amounts of capital being spent?

There are, inevitably, no definitive answers. AI monetisation remains uncertain; enterprise adoption is still early stage, and the path from technical capability to durable earnings is unlikely to be linear. Meanwhile, demand for AI-related infrastructure continues to rise, as competition intensifies to build larger and more capable models.

While the range of potential outcomes remains wide, one feature of the current cycle that stands out is the pace of consumer adoption. Since the public release of ChatGPT in late 2022, AI tools have reached global scale faster than previous platform technologies. GPT has approached 800 million weekly active users in under two years, with similar adoption rates for Google’s Gemini. Social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram took the better part of a decade to achieve the same scale.

The comparison with social media, however, only goes so far. Social networks reshaped how people communicate and consume information, embedding themselves into daily life. Yet for all their cultural impact, they did little to improve economy-wide productivity in the way that electricity, the internal combustion engine or the personal computer once did. Comparisons across technologies are inevitably imperfect, and AI’s promise lies in more than consumer engagement; it is rooted in augmentation and the potential to enhance human capability across a wide range of tasks. That broader economic potential underpins much of today’s excitement, even as the timeframe for AI’s full realisation remains uncertain.

The more important distinction lies in how these technologies scale. Social media expanded rapidly by piggybacking on top of existing internet and mobile infrastructure, allowing growth with relatively modest incremental physical requirements. AI does not benefit in the same way. As models become more capable and usage broadens, scaling AI requires very substantial (and costly) new physical infrastructure and rapidly rising energy inputs, binding progress directly to the availability of power[1].

This raises a broader and increasingly consequential question. What energy system can credibly support the continued scaling of AI while aligning with corporate decarbonisation objectives?

For the technology companies at the centre of this shift, including those held in our portfolios, this tension is already shaping their decisions. Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta are expanding data centre footprints at pace while maintaining ambitious targets to reduce their environmental footprints, bringing the question of power sourcing into focus. This quarterly explores how those choices are being made.

It’s all about power

In a previous Responsible Investment report, Power Hungry AI, we examined the rising energy intensity of data centres. The report looks at the forces driving AI’s energy consumption and the implications for grid resilience and corporate decarbonisation goals. What has changed since last year is the scale and urgency of the challenge we highlighted. Capital commitments and compute requirements continue to increase, meaning AI workloads are driving electricity demand at a pace power systems were simply not designed to absorb.

U.S. data centres already consume around 4-5% of America’s total electricity, with Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta, accounting for ~1% alone[2]. The U.S. Department of Energy projects this former figure could more than double by 2028, as AI adoption broadens. This growth is challenging because the U.S. power system was not built with significant spare capacity. After decades of subdued demand, investment focused on efficiency rather than expansion, leaving the grid ill-prepared for large new loads. The result is that incremental data centre demand is placing disproportionate strain on local grids, accelerating the need for new generation and infrastructure.

For our tech holdings, the resulting power challenge is not just one of scale, but also one of reliability. These companies are among the world’s largest corporate buyers of renewable energy with wind and solar forming the backbone of their decarbonisation strategies[3]. However, AI workloads place demands on power that intermittent generation alone cannot meet.

Training frontier AI models and running inference at scale requires data centres to operate continuously at very high and variable loads. This is because AI training is compute-intensive and workloads are uneven, with large training runs starting and stopping around the clock, meaning data centres must operate continuously while managing rapidly fluctuating power demand. Renewable generation is inherently weather-dependent and cannot guarantee availability on an hourly basis. In the absence of large-scale, commercially viable battery storage, this mismatch has had to be bridged by other sources of reliable power. Today, that role is largely being played by natural gas, with a growing preference for co-located gas turbines because of their reliability, speed of deployment and ability to respond flexibly to demand.

While renewable power purchase agreements allow companies to offset emissions on an annual basis, they do not ensure that electricity is carbon-free at the point of consumption. For technology companies pursuing true 24/7 clean energy, an explicit ambition for both Alphabet and Microsoft by 2030, that distinction matters, and is increasingly shaping how their energy procurement strategies evolve.

Nuclear renaissance

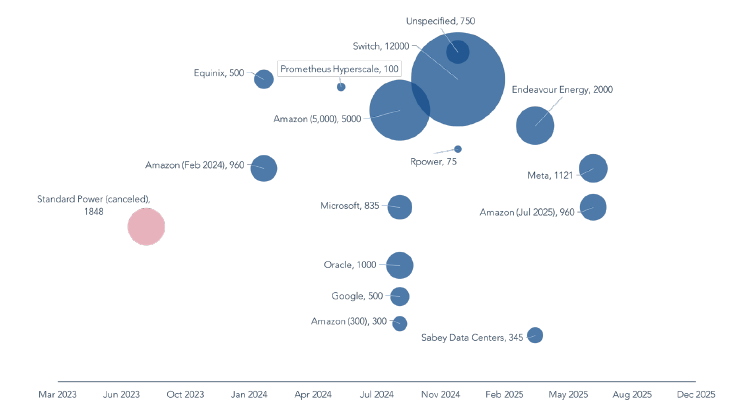

Only a small number of energy sources can deliver electricity that is both low-carbon and reliably available around-the-clock. These include hydro, long-duration storage, and nuclear. Hyperscalers are beginning to recognise nuclear’s strategic value. This is reflected in the growing number of long-dated nuclear power purchase agreements signed over the past year and, in some cases, direct support for the restart, life extension or uprating of existing reactors (Figure 1). Industry analysis estimates that roughly 14% of the ~84 GW of clean power contracted by Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta in the U.S. comes from nuclear sources[4].

Figure 1: U.S. Nuclear Power Announcements Tied to Data Centres and AI

Source: BNEF, Press Releases, RBC Capital Markets, 31 December 2025. The reference to specific securities in this slide is not intended as a recommendation to purchase or sell any investment.

Perhaps the best illustration of how seriously hyperscalers are treating their power constraint is the revival of Three Mile Island. In 2024, Microsoft signed a long-term power purchase agreement with Constellation Energy to support the restart of the reactor. These multi-decade, often above-market contracts are not about short-term economics. Rather, they reflect a clear strategic priority which is to secure firm, carbon-free power for the long-term to sustain AI load growth.

Big tech has effectively become an anchor customer for the United States’ existing nuclear fleet. This has meaningful implications. Nuclear plants have historically struggled in deregulated markets, squeezed by cheap natural gas and subsidised renewables. Long-term commitments from hyperscalers help stabilise revenues, improve nuclear plant economics and enable licence extensions, preserving a source of firm, low-carbon capacity that might otherwise have been retired.

Interest in nuclear power is also being reinforced by a renewed policy focus. Nuclear already supplies around 18% of U.S. electricity from the country’s 94 operating reactors. Recent policy signals have emphasised the role of maintaining and expanding this capacity with the Trump Administration signalling support for 10 new reactors to be built by 2030.

This shift is not occurring in isolation. After two decades of subdued electricity demand, with U.S. consumption growing at just ~0.7% per annum since 2000, well below GDP growth, a structural increase in electricity demand is emerging. Industrial reshoring, expanded domestic manufacturing, and the rapid growth of data centres are driving this. Nuclear is therefore increasingly viewed as a strategic component of the United States’ future energy mix.

Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that valuations across nuclear-exposed companies have risen over the last year. However, this renewed enthusiasm risks obscuring a more prosaic reality – nuclear is not a near-term solution. New reactors require long permitting timelines, extended construction periods and significant upfront capital. As a result, while nuclear’s role in the energy system is likely to expand, its resurgence will be incremental rather than immediate.

Hold your horses

As a result, nuclear power plays a critical but constrained role in the AI energy stack. Nuclear plants provide reliable, carbon-free baseload electricity, operating most efficiently at steady output over long periods. This makes them well suited to deliver a 24/7 clean power system, but less effective at responding to the highly volatile, minute-to-minute demand fluctuations that characterise large-scale AI training workloads. While some modern reactors can adjust output within the course of hours, they are not designed to ramp quickly in response to sudden changes in load. As a result, nuclear is best understood as a foundational layer rather than a complete solution to the energy dilemma. Other technologies will therefore be required.

Attention is increasingly turning to next-generation nuclear technologies like small modular reactors (SMRs) and, further out, nuclear fusion. SMRs are designed to be smaller, factory-built on-site and potentially quicker to deploy than conventional reactors. They will have greater flexibility and much lower upfront capital requirements than traditional reactors. For data centre operators, this modularity is very appealing.

Google has signed corporate agreements linked to small modular reactors with Kairos Power, targeting initial capacity around 2030. OpenAI founder Sam Altman is a co-founder of SMR developer Oklo, while Bill Gates has his own advanced reactor designs via his company, TerraPower.

Despite this high-profile support, SMRs remain at an early stage of commercialisation. Few projects are operating at scale, and timelines are measured in the 2030s rather than the nearer term. Nuclear fusion sits even further out. While recent scientific breakthroughs are encouraging, fusion is unlikely to contribute meaningfully to commercial power supply for decades. Together, these technologies point to the direction of travel, towards firm, abundant, low-carbon power. However, neither resolves the immediate energy constraints facing AI today.

The long arc of progress

Vaclav Smil’s observation at the start of this Report is useful to anchor this discussion. As systems grow more complex, their energy requirements grow. AI is proving no exception. For the tech companies held in our portfolios, namely Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta, the power question is already shaping their strategies, capital allocation decisions, and long-term risk management.

Their response spans renewable procurement, gas as a near-term bridge, and a growing engagement with nuclear. Taken together, these choices reflect a pragmatic attempt to reconcile rapid AI growth with longer-term environmental responsibilities. Nuclear’s re-emergence in this context is telling. It is neither a silver bullet nor a near-term solution, but signals how seriously the energy constraint is being taken.

There is unfortunately no single technology that can meet AI’s power requirements in isolation. The path forward is inherently hybrid combining renewables, battery storage, flexible generation and, over time, hopefully advanced nuclear, with each operating on different timelines and serving different roles. The power challenge inevitably complicates Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta’s climate commitments, but does not render their targets obsolete.

Patience is needed in this transformation. The pace of AI’s development is a testament to human ingenuity, and we are hopeful that its next phase will be shaped not just by better models, but by better energy systems. Directing the same creativity and capital towards solving the power challenge, will of course take time. Future advances may reduce AI’s energy intensity through more efficient models, improved hardware or entirely new architectures. Technological progress has repeatedly defied linear expectations in the past, and as history suggests, when innovation is aligned with necessity, it has a habit of advancing. We remain open-minded to all potential outcomes.

In this context, we think that scale really matters. The companies best positioned to navigate AI’s energy dilemma are those with the financial capacity, technical depth and agility to engage across the energy system. Working with partners from utility and grid operators to nuclear developers and storage providers will be critical to success. This reinforces why leadership in AI will likely be shaped by more than model capability alone. Securing reliable, scalable and low-carbon energy will become a source of competitive advantage. This advantage is often built on early foresight, Microsoft, for instance, signalled its intentions years ago by acquiring land with strategic access to power. This dynamic is naturally favours global tech companies like Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta, whose scale and balance sheet strength enable them to invest behind the solutions they need. Observing how our portfolio companies address this challenge is central to both our understanding of their strategy, capability and our conviction in their long-term adaptability and resilience.

[1] Future AI energy demand will depend on how the technology and the economics evolve. If models become significantly more efficient, or if investor appetite for ever-larger training runs fades, power requirements could be lower than implied here. Equally, wider adoption of AI could drive much higher inference demand. This analysis reflects how AI is being built and used today, recognising that these assumptions may change as the technology matures.

[2] Barclays Research

[3] Jefferies Research

[4] S&P Global

Further information relating to how ESG integration is applied to the fund can be found in the fund prospectus and investor disclosure document. For further information relating to Troy’s approach to company voting and engagement, please see Troy’s Responsible Investment and Stewardship Policy available at www.taml.co.uk.

Please refer to Troy’s Glossary of Investment terms here. The document has been provided for information purposes only. Neither the views nor the information contained within this document constitute investment advice or an offer to invest or to provide discretionary investment management services and should not be used as the basis of any investment decision. The document does not have regard to the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. Although Troy Asset Management Limited considers the information included in this document to be reliable, no warranty is given as to its accuracy or completeness. The views expressed reflect the views of Troy Asset Management Limited at the date of this document;

however, the views are not guarantees, should not be relied upon and may be subject to change without notice. No warranty is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information included or provided by a third party in this document. Third party data may belong to a third party. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. All references to benchmarks are for comparative purposes only. Overseas investments may be affected by movements in currency exchange rates. The value of an investment and any income from it may fall as well as rise and investors may get back less than they invested. The investment policy and process of the may not be suitable for all investors. Tax legislation and the levels of relief from taxation can

change at any time. References to specific securities are included for the purposes of illustration only and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell these securities. Although Troy’s information providers, including without limitation, MSCI ESG Research LLC and its affiliates (the “ESG Parties”), obtain information from sources they consider reliable, none of the ESG Parties warrants or guarantees the originality, accuracy and/or completeness of any data herein. None of the ESG Parties makes any express or implied warranties of any kind, and the ESG Parties hereby expressly disclaim all warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, with respect to any data herein. None of the ESG Parties shall have any liability for any errors or omissions in connection with any data herein. Further, without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall any of the ESG Parties have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages. All reference to FTSE indices or data used in this presentation is © FTSE International Limited (“FTSE”) 2025. ‘FTSE ®’ is a trademark of the London Stock Exchange Group companies and is used by FTSE under licence. Issued by Troy Asset Management Limited (registered in England & Wales No. 3930846). Registered office: 33 Davies Street, London W1K 4BP. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FRN: 195764) and registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) as an Investment Adviser (CRD: 319174). Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

© Troy Asset Management Limited 2026