Unplayable

The real trouble with this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable but not quite. Life is not an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians. It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is; its exactitude is obvious, but its inexactitude is hidden; its wildness lies in wait

GK Chesterton

So-called ‘Liberation Day’ on 2nd April saw a continuation of the predictable unpredictability characteristic of Donald Trump. This has been exhausting to many, irritating to some and pleasing to others, who had hoped and expected this administration to follow through with his trade policies. Whilst the S&P 500 was an important barometer of success for the president during his first term, it is not yet clear which yardsticks will carry the greatest weight this time around.

Scott Bessent, his new Treasury Secretary, says that Main Street, not Wall Street, is the priority. There has been plenty of gnashing of teeth at the apparently self-destructive policies instigated since the inauguration but perhaps the new politics is merely symptomatic of our times. We are discovering that democracy is user sensitive. Yet markets loathe the inconsistency and unpredictability created by the disrupter in chief.

The Forgotten Man

Politics and geopolitics are relevant once more. It is evident that President Trump is attempting to (at least partially) dismantle the post-war financial system. The prioritising of Main Street has been a long time in coming. (Remember ‘Occupy Wall Street’ of 2011?) As Mr Bessent warns, ‘after 20, 30, 40, 50 years of bad behaviour you can’t just wipe the slate clean’. US middle and lower earners have been left behind for decades. The Gini Coefficient[1] informs us of income inequality by country and has been rising in the US since 1980. The MAGA movement’s focus on ‘flyover’ and ‘rust belt’ states aims to address those forgotten and left behind by a globalised economy. Certainly, when it comes to trade policy experiments, whether carefully thought out through four-dimensional chess or as a shooting from the hip negotiating tactic, markets will rightly question whether the consequences of such radicalism have been fully and carefully considered.

The End of an Era

We have referred to regime change in previous reports going back to 2022 (see Investment Reports 71 & 73). This is an environment where it is better to be looking from 30,000 feet than to be down in the weeds. Ignore the macro at your peril. President Trump’s actions reverse decades of US stability and the post 1989 peace dividend to boot!

I began my career in 1989, a month before the fall of the Berlin Wall. This gave the world economy a supply shock, as labour and commodities arrived from behind the former iron curtain. It was disinflationary and pro-growth. In addition, the peace dividend, not always obvious, gave a tailwind to the economy. By way of example, UK spending on defence fell from 4% of GDP in 1989 to a low of 1.8% by 2018 (according to the World Bank). Globalisation ripped. The US announcements regarding Ukraine, European defence and tariffs highlight that we are now in a new world. The outcome of this regime change is likely to be higher bond yields and stickier inflation. Rising bond yields raise the cost of capital and are likely to challenge high equity valuations. There has been a shift, within just a few weeks, from trade wars to capital wars.

Tarrifying

Tariffs are not liberating. Far from it. The axiomatic benefits of free trade and ‘comparative advantage’ are being relearned as we dust off our old economic texts. We should not be surprised that President Trump buys into these trade policies. He has espoused the virtues of tariffs for almost forty years, dating back to when Japan was challenging the pre-eminence of the US in the late 1980s, and long before China was the exporter of choice for manufactured goods. Yet tariffs are a very blunt instrument. While his aims may be worthy to protect the forgotten man and domestic manufacturing while promoting foreign direct investing and raising taxes – the second and third order results can be counterproductive and highly damaging.

Assuming tariffs raise inflation, US consumers will struggle as their spending power decreases. Some uncompetitive domestic businesses will benefit in industries where tariffs bring imports to a halt. Job losses are likely as large capital investments and hiring plans are put on hold due to the uncertainty. Most companies will suffer, as input costs rise and margins are squeezed. Stock markets, which had been looking through the lens of Trump’s first presidency, had not anticipated the size and scale, nor impact, of these measures. Recession risks are rising, and a downturn has shifted from the possible to the probable. Recessions tend to be the result of tighter monetary policy but, as a trade policy experiment is the catalyst here, it is less certain that looser monetary policy will solve the problems. It is not clear that business confidence will return with lower interest rates.

We do not believe markets are pricing in a recession. The average fall of the S&P500 in a recession is -31% and the index is now down -10%[2] (as at 28 April) . Historically, the stock market has never troughed before a recession has started and the average bottom has occurred seven months into the downturn. Moreover, the valuation starting point in January was at an extreme, as measured by the cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio (CAPE). At 37 times[3], this multiple had only been exceeded twice historically – once during 1999, at the height of the dot com boom (44x), and once towards the end of 2021 (38x). The US stock market fell c. -50% after the 2000 peak despite a relatively mild recession. The bull case today must be for a quick reversal of policy but there remains the question of how much damage has already been done to the credibility of the US.

Further downside seems likely despite sharp rallies, which are so common in bear markets. Notwithstanding the recent falls, valuations are still stretched and there must be heightened risk to corporate earnings as growth slows. The ‘E’ (earnings) of the ‘P/E’ (price to earnings) ratio must be viewed with scepticism. The combination of falling earnings and valuations is not a good one.

A lack of credibility

Following the April 2nd tariff announcements bond markets experienced their largest three-day surge in yields since 1982. Scott Bessent indicates a desire to manage Treasury yields lower. Yet this price movement confirmed to us that we remain in a bond bear market.

Bond markets matter to stock market investors. In a world of low inflation, investors are prepared to fund a government even at low yields. This is what we experienced for much of the 2010s. With the threat of higher inflation, holders of bonds will ask for a higher return on their capital, especially when supply is inflated. It was, after all, bond investors that called time on Liz Truss’s premiership in 2022. They were spooked by increased borrowing and tax cuts, raising the supply of gilts. The US playbook looks little different except for the dollar having the luxury of being the world’s reserve currency. Today’s bond investors are once again speaking truth to power.

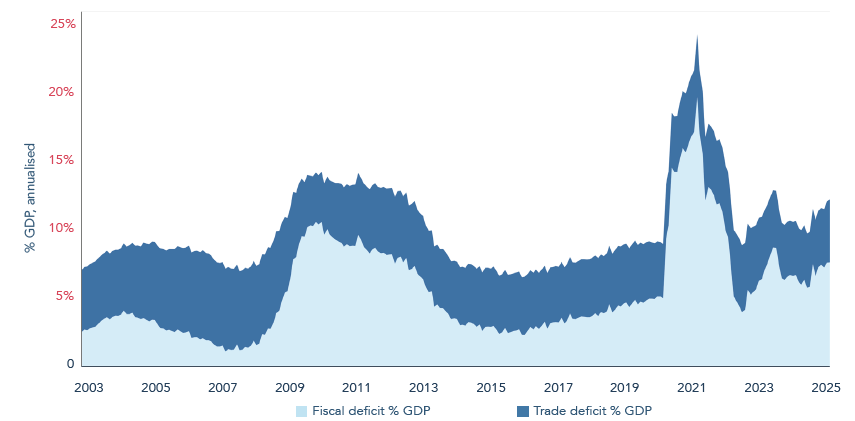

Trump and Bessent may have correctly identified America’s Achilles’ heel. This comes in the form of the country’s fiscal and trade deficits (see Figure 1) and its reliance on the kindness of strangers for funding its debt. Markets are suggesting that America may have overplayed its hand, with yields rising, the dollar weakening and the gold price appreciating. Did the administration anticipate the knock-on effects of trade wars, leading to a shift in capital flows? No one knows who is selling Treasuries, but foreigners own 30% of US government debt outstanding. Meanwhile foreign capital in the stock market has surged in recent years to almost 20% of US equities (see Figure 2). These investors may now be voting with their feet.

Figure 1 – Annualised fiscal deficit and trade deficit as % of GDP

Source: US Census Bureau, 31 March 2025. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Figure 2 – Foreign Ownership of US Equities

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 31 December 2024. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Ironically, countries such as China, Japan and the European Union that have trade surpluses with the United States, were, hitherto, happy to recycle their dollars back into US financial assets. Trade wars have given them less reason to do so and have thereby accelerated regime change further.

‘Our currency, but your problem’

The US dollar has been our friend for much of the past two decades. During periods of market turbulence in 2008, when the pandemic hit in 2020, and most recently in 2022 when stocks and bonds fell sharply, the greenback has ridden to our rescue, providing an offset to falls elsewhere. A firm dollar also dampened volatility during the Asian crisis in 1997 and the Russian and LTCM defaults in 1998.[4] However, the dollar has not stuck to the script as an offset in 2025. As trust breaks down, confidence in the dollar may wither. The unsustainability of US government debt seems, at last, to be catching up with it. We know from the mooted ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’ that there is a desire to weaken the dollar. We have materially reduced our dollar exposure to take account of the rising risks.

There are few obvious offsets. Gold has been kind, but it is not always predictable. Bonds have been pretty useless as yields have risen, although index-linked give us some shelter from inflation. Some equities have held up, especially those that are in less crowded trades. We have taken the decision to reduce our duration in US TIPS from less than five years to less than three years. This will improve our liquidity and make us even less vulnerable to rising yields. We have also added a new holding in the Japanese yen, which we expect will behave more reliably as a safe haven in periods of stock market stress.

Reefs tied

The outlook has become considerably more uncertain. Companies and consumers have shifted from confidence to hesitancy. We were prepared for more treacherous waters and had our reefs tied. Equity valuations offered little support, but it is always hard to see where the catalyst would come from to offer realism.

We do not try to precisely predict the future. Policies can be reversed on a whim, but the damage done may not so easily be undone. Back in 2008 we took materially more equity risk. Valuations were compelling. Today, following the correction from all-time highs, they are mildly better than poor at a market level. We have selectively added to our equity exposure (c.7% since quarter end) in a handful of businesses where long-term returns have become more attractive. We did this in the expectation that we are likely to be early and that timing the bottom is a mug’s game. We will continue to be guided by long-term valuations and select bottom-up opportunities, while sticking firmly to our qualitative bias.

A recession, if it comes, is likely to lead to greater uncertainty, lower prices and better value. Nothing is certain but in such circumstances our allocation to equities will rise, possibly substantially.

The Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930 were widely seen as exacerbating the Great Depression. They were soon revisited after a change of government but ultimately took years, even decades to unwind. During peak globalisation there was much talk of the world getting smaller. For all the talk, the world just got larger and less reasonable.

[1] The Gini Coefficient is a measure of inequality, commonly used to gauge income inequality within a population.

[2] Bloomberg, from year to date Index peak on 19 Feb 2025

[3] http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm

[4] In August 1998, the Russian financial crisis, which involved Russia defaulting on its debt and devaluing the ruble, triggered a major crisis for the Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) hedge fund. LTCM, a highly leveraged fund, held significant positions in Russian government bonds, and the sudden market turmoil led to massive losses. The losses threatened to collapse the fund and trigger a global financial crisis, prompting a bailout by a group of banks and the Federal Reserve.

Disclaimer

Please refer to Troy’s Glossary of Investment terms here. The information shown relates to a mandate which is representative of, and has been managed in accordance with, Troy Asset Management Limited’s Multi-asset Strategy. This information is not intended as an invitation or an inducement to invest in the shares of the relevant fund. Performance data provided is either calculated as net or gross of fees as specified. Fees will have the effect of reducing performance. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. All references to benchmarks are for comparative purposes only. Overseas investments may be affected by movements in currency exchange rates. The value of an investment and any income from it may fall as well as rise and investors may get back less than they invested. Neither the views nor the information contained within this document constitute investment advice or an offer to invest or to provide discretionary investment management services and should not be used as the basis of any investment decision. There is no guarantee that the strategy will achieve its objective. The investment policy and process may not be suitable for all investors. If you are in any doubt about whether investment policy and process is suitable for you, please contact a professional adviser. References to specific securities are included for the purposes of illustration only and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell these securities. Although Troy Asset Management Limited considers the information included in this document to be reliable, no warranty is given as to its accuracy or completeness. The opinions expressed are expressed at the date of this document and, whilst the opinions stated are honestly held, they are not guarantees and should not be relied upon and may be subject to change without notice. Third party data is provided without warranty or liability and may belong to a third party.

Although Troy’s information providers, including without limitation, MSCI ESG Research LLC and its affiliates (the “ESG Parties”), obtain information from sources they consider reliable, none of the ESG Parties warrants or guarantees the originality, accuracy and/or completeness of any data herein. None of the ESG Parties makes any express or implied warranties of any kind, and the ESG Parties hereby expressly disclaim all warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, with respect to any data herein. None of the ESG Parties shall have any liability for any errors or omissions in connection with any data herein. Further, without limiting any of the foregoing, in no event shall any of the ESG Parties have any liability for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential or any other damages (including lost profits) even if notified of the possibility of such damages.

All references to FTSE indices or data used in this presentation is © FTSE International Limited (“FTSE”) 2025. ‘FTSE ®’ is a trade mark of the London Stock Exchange Group companies and is used by FTSE under licence. Issued by Troy Asset Management Limited, 33 Davies Street, London W1K 4BP (registered in England & Wales No. 3930846). Registered office: 33 Davies Street, London W1K 4BP. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FRN: 195764) and registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) as an Investment Adviser (CRD: 319174). Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Any fund described in this document is neither available nor offered in the USA or to U.S. Persons.

© Troy Asset Management Limited 2025.